Monday, 13 June 2011

Migration

With that in mind I've migrated my blog to http://cradledincaricature.wordpress.com/. First post went up yesterday > http://cradledincaricature.wordpress.com/2011/06/12/soja-geography-la-sarthe/.

Information relating to the Cradled in Caricature symposium will remain here for the meantime, though will to be migrated from 20 June onwards. And for those who are interested, the #CiC liveblog on 20 June will be simulcast between the new CiC wordpress site and @cincaricature. Exciting times!

Dr B

Wednesday, 8 June 2011

#CiC – adverts and taxonomies

Despite there being a clear intellectual rationale behind this workshop focusing on cigarette advertising in the 1920s (see abstract here), we felt that spreading posters containing the Marlboro man around campus may have attracted some negative attention from the powers that be at the University of Kent. We therefore had to find an alternative advertising campaign that was both well known internationally and clearly associated the product in question with making people a 'better' man/woman. After some thought, the only campaign we could think of was what you see below. As Terry Norton says on Knowing Me Knowing You with Alan Partridge “people will always want to look at lovely ladies”...

Cradled in Caricature will take place on Monday 20 June, at Woolf College, University of Kent, Canterbury.

The full programme can be found here.

For inquiries or further information please contact me at cradledincaricature@gmail.com or twitter.com/cincaricature.

Tuesday, 7 June 2011

Memory and Remembrance - Part 1: The Fallen

One sub-theme within this group looks at physical and imaginative memories of 'The Fallen' and how they both shape and are manipulated by politics and culture. A taster of this work can be found below...

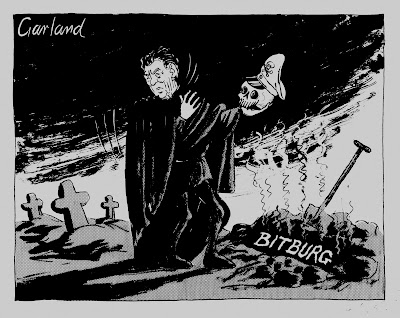

(c) British Cartoon Archive, University of Kent, Nicholas Garland, Daily Telegraph, 30 Apr 1985.

As Jay Winter writes, however we might wish to believe otherwise, remembrance is political. When US President Ronald Reagan visited West Germany in Spring 1985 to mark the 40th anniversary of VE Day his choice of locations (and indeed those of his host Chancellor Helmut Kohl) were consciously political, chosen to foster reconciliation by establishing the events of World War Two as a shared tragedy (these one time combatants were now, of course, allies). The itinerary however included a visit to Kolmeshohe Cemetery at Bitburg, a site at which 49 members of the Waffen SS were buried. When this was leaked to the press a huge controversy ensued (interestingly Reagan’s chief of staff, Michael Denver, had failed to notice the names on the graves on a preparatory visit due to heavy snowfall). Despite protests from Jewish Americans, Reagan pressed on with the visit and joined Kohl on 5 May 1985 to lay wreaths at a wall of remembrance.

The visit was ‘saved’ by former Nazi Luftwaffe pilot and later NATO General Johannes Steinhoff, who in an impromptu act reached and shook the hand of his former belligerent General Matthew Ridgway, commander of the 82nd Airborne during World War Two. This, alongside a well pitched speech from the ever theatrical Reagan, gained the visit unexpected credit. Garland anticipates how Reagan was expected to emerge from the Bitburg, using the exhumation of Yorick in Shakespeare’s Hamlet to mock Reagan (who famously was a Hollywood actor before turning to politics). While Hamlet touchingly remembers the court jester he once knew, Reagan turns in horror from the Nazi before him (which, as a side note, is possibly a visual quotation to the Nazi villains in Steven Spielberg’s 1981 film Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, one of the highest-grossing films of the decade).

Sunday, 5 June 2011

#CiC - heroes and villains

Their abstracts (below) inspired the above poster which now can be found dotted across UKC.

Jacob Bradsher

Villainous caricature in Science-fiction literature, film, and art is rooted firmly in the portrayal of villains in Victorian literature. The limitations of the human mind to conceive of truly unique villainous characteristics is obvious when these comparisons are made. Despite the radical design of some twentieth century visions of space-villains and alien overlords, the similarities between them and the likes of Dickensian illustrations are striking.

I would like to investigate what makes a ‘villain.’ That is, I am going to explore the facial features, actions, modes of speech, and overall physical appearance of what has been considered villainous in Victorian literature (such as the illustrations of Phiz and Cruikshank) and how that has carried over into genres like science fiction and the portrayal of its antagonists (Star Wars, Titan A.E. etc.).

It’s mostly a compare/contrast project, but I don’t want to simply show the similarities and differences in illustrations and character designs. Roughly, I would be using Dickensian canon as a starting point, then I would move to the golden age of American comic books, then onto modern movies and science fiction literature to explicate the relationship between the genres and periods.

Basically, I would like to explore the relationship between what stereotypical villainous characteristics are immediately available to us a humans and those that we project onto perceived villains of the future. The caricatures of Dickensian villains are easily identifiable compared to some of those featured in Sci-Fi productions, but there are also striking similarities.

Caleb TurnerCradled in Caricature will take place on Monday 20 June, at Woolf College, University of Kent, Canterbury.

How do we view bodily depictions through caricature? The cartoonist Lenn Redman has described caricature as: “An exaggerated likeness of a person made by emphasising all of the features that make the person different from everyone else. It is not the exaggeration of one’s worst features. This is a carry over from the days, 100 years and more ago, when humour was almost always based on cruelty and when the caricaturist’s intent was to insult his subject… Many people think that a caricature is necessarily a graphic distortion of a face. Not true! The essence of a caricature is exaggeration – not distortion. Exaggeration is the overemphasis of truth. Distortion is a complete denial of the truth.

In this light, caricature should no longer be (traditionally) viewed as simply a form of mockery through grotesquery, but more so as magnifying the truth through over-emphasising the defining physical boundaries – constituting an individual body – to their absolute limits. One type of body in particular that utilises this process to great effect is the superhero figure, being an intensely graphically illustrated physicality.

To exaggerate a super-body is to take one’s most distinguishing features, (i.e. pointed ears, thick eyebrows, thin chin, warped smile and sharp teeth for the face of ‘The Green Goblin’; huge, thick fists attached to tree-trunk muscular arms for the hands of ‘The Incredible Hulk’) and streamline them to depict just how ‘different from everyone else’ they are. To caricaturise these individuals is to then ‘magnify’ the limits of truth associated with them even further (i.e. a display of ‘invulnerability’ in the sheer size of Superman’s solid chest, or ‘intelligence’ with Brainiac’s brain bulging outwards from the top of his head).

What does this overemphasis of truth (rather than distortion) achieve in conveying meaning to us through the process of caricature? The superhero body is itself an expression of deliberately exaggerated characteristics, intended to evoke from only a marginal threshold of interpretation, consequently having a specific series of connotations attached to it. These constructed figures portray specific ideas, but they are designed to be among the most recognisable depictions of these ideas: they are presented as being an absolute epitome or incarnation of such concepts.

How, then, is this ‘magnification’ of super-bodily attributes useful as a process for understanding and why as viewers do we need it to better realise a sense of meaning or truth?

The full programme can be found here.

For inquiries or further information please contact me at cradledincaricature@gmail.com or twitter.com/cincaricature.

Thursday, 2 June 2011

Richard Rodger: Space, place and the city: a simple anti-GIS approach for historians.

Watching this Digital History seminar at the IHR is therefore part of my job. Thus I thought I'd share.

The Efflorescence of Caricature

First, I wanted to praise the IHR for providing such a reactive and reflexive space as RIH. I first saw this book at BSECS '11 (which was in early January), asked for a copy days after, recieved it just a few days after that, and having only submitted the review to them in mid-April it is already up. So huge kudos to the IHR.

Second, I wished to add that I really did enjoy this book even if at times my review comes across as a little negative. There were some moments of signifcant frustration with the 'representation without physical grounding' direction some of the contributions took (my flatmate can verify to one particular moment where the book was in risk of being hurled out of a room - I'm sure you can guess which from the review...), but the willingness of Porterfield in particular to break the study of graphic satire out of the shackles of orthodoxy must be applauded. So if you like your history to be both annoying and inventive (comes with the territory of being radical I guess), then pick up a copy.

Monday, 30 May 2011

Flirting with Apocalypse - Part 3: Whales

On Tuesday 21 July 1981 the International Whaling Commission met at Brighton's Metropole Hotel for their annual conference. On the agenda was a worldwide ban on the commercial killing of whales. Japan led a successful opposition to the proposals, and despite nations voting 16-8 in favour of a ban with three abstentions, the requirement of a three-fourths majority ensured the ban did not pass.

Saturday, 28 May 2011

#CiC - what makes masculinity?

Next week postgraduate students at the University of Kent will find in their email inbox a copy of our programme. The team are very proud of the contributions we've managed to collect together, coming as they do from across the postgraduate community at UKC. We hope the community will respond with the same enthusiasm we have.

Part two of the promotion drive will see a collection of posters appear around campus highlighting the themes we intend to explore during the day. These are designed to be big, bold and provocative, but also to make serious points whilst provided discursive links with the contributions of specific speakers.

This poster plays on the themes Stelios Christodoulou, a PhD candidate in Film Studies at UKC, will explore in his paper '“You can tell by the way I use my walk, I’m a woman’s man: no time to talk”: 70s Masculinities in Saturday Night Fever (1977)'. His abstract reads thus:

If there is single image that encapsulates the 70s model of masculinity in popular culture, this is arguably John Travolta on the disco floor, in his white three-piece suit and black body shirt, right hand pointing upwards. Travolta’s performance as Tony Manero in Saturday Night Fever (1977) elevated him to immediate stardom and now stands for all polyester fakery and excess tastelessness that allegedly was the 70s. What popular memory has obscured, however, is that Tony Manero’s masculinity is by no means an accurate reflection of the 70s, but a construct, an amalgam of often contradictory masculine styles and behaviours.

This paper explores the construction of Tony Manero’s masculinity, aiming to explain its cultural function and popularity, rather than to expose stereotypes. It also uses Saturday Night Fever as a historical case study of masculine identities in the late 70s. Underpinning the film are a number of historically specific discourses, including the association between disco and homosexuality, the male liberation movement, the style of the gay clone, Travolta’s star persona, and the revival of white ethnicity.

These discourses manifest in the film’s memorable grooming scene, which serves as the paper’s main textual example. The paper considers existing interpretations of this scene and attempts new interpretations based on literature on the representation of masculinity, including Richard Dyer’s discussion of the male pin-up. The scene, however, proves resistant to a theoretically consistent ‘reading’. Rather, it reveals that Tony Manero’s masculinity collapses together disparate signifiers of 70s liberated and homosexual masculinities with a nostalgic understanding of a unitary model of aggressively heterosexual machismo. The paper ends with the proposal that Tony’s identity as an Italian-American working class man renders his implausible masculine identity both appealing and believable.

Tuesday, 24 May 2011

Neurogubbins: Goffman vs bad science

His paper went something like this.

Erving Goffman is wrong, the world is not a stage. The idea that social interaction/culture can 'replace' nature makes little evolutionary and/or cognitive sense, as nature and nurture are intertwined. Thus reality is not wholly socially constructed, rather our actions are a combination of acting roles (the illusion bit) and self; imitations are not illusions; the subjunctive worlds humans create are real; and so on and so forth.

Now, I'm not sociologically 'trained' enough to respond to this fully [though I would consider the proposition that I couldn't respond without sufficient training somewhat narrow minded], but I did find McConachie persuasive and engaging, especially in his belief that sociology could learn a lot by spending some time revisiting anthropology. Where I did find McConachie problematic however was in his appeal to science for some form of subterranean authority.

As my problems with the paper grew steadily, it seems prudent to outline them in turn, in the creeping chronological order in which they appeared.

First, in his initial criticisms of social constructivism, McConachie seemed happy to lump together the biological, the cognitive and the evolutionary. Now these fields obviously have their points of interaction, but his reductionism was undoubtedly crude.

Second, McConachie described empathy as the reading of a persons mind. And to give this statement some sense of gravitas he mentioned 'mirror neurons'. Later he used the concept of 'neural plasticity' as one reason why “we become out habits” [at which point he also seemed to be contradicting his attack on Goffman entirely...]. More on both these scientisms later. He also, continuing the 'mind' theme, stated, again as a counter to Goffman, that “our brains are part of the real world”. I have no problems with this statement. What I do have a problem with is his assumptions that the only alternative to this belief is Cartesian dualism. It is not (see Raymond Tallis).

Third (and this all came out in the Q&A session, when perhaps McConachie was being less cautious with his words), he stated that mirror neurons are the “lower level of empathy” on Thompson's scale (see Evan Thompson, Mind in Life, 2007), and that in order to perform well “actors [that being those on a stage] must work closely with the mirror neuron of other actors”.

Gradually then, although carefully avoiding the term 'neuroscience', McConachie descended into neuromania. Whether or not one believed his reading of Goffman and his alternative views on social interaction, this appeal to (neuro)science as subterranean empirical evidence is false. Mirror neurons are no longer considered as unproblematic as they were upon their 'discovery' in 1992; and neural plasticity has been widely derided as a term without meaning (see here). McConachie's understanding of (neuro)science is therefore deficient to the point of alarmingly basic. Moreover, recent neuroscience, and in particular the work of David Eagleman, might actually be in the process of providing evidence to prove Goffman's thesis. Eagleman is a divisive figure, but if his work on time and perception is right, that (in sum) there is a distinct gap between reality and perception during which time the brain filters and manages the information it is receiving before reporting an alternative 'reality' back to the host, then Goffman is back in the game (see here).

My problems with the paper are simple. Why do figures such as McConachie think reaching to a limited understanding of neuroscience for answers is a positive step in humanities scholarship? McConachie's paper was, after all, admirably inter/multi/trans/post-disciplinary [is anyone else bored of such shifting nomenclature?] and hence neuroscience was not needed to support his point (though studies of evolution and psychology clearly were, and indeed made welcome appearances). Indeed why place alongside a rich and diverse understanding of sociology, anthropology, psychology, philosophy et al, subterranean observations on a discipline towards which he clearly has limited, partial and hardly cutting edge knowledge of.

Much more work is needed to understand how and for what purpose humanities scholars - who I think we can safely say work in a field whose paradigm shifts tend to slow and tortuous - can logistically draw upon a field as fluid, radical, fresh, disrespectful towards meta-narratives and developing at such a breathtaking pace as neuroscience. Put McConachie in front of a room of scientists and I suspect that his subterranean scientism would have been uncovered more readily, and his paper, respectfully, put under severe scrutiny.

Monday, 23 May 2011

Pantomime Parliamentarians

Tuesday, 17 May 2011

OP and Jewishness

Some background. On Monday 9 October 1809 John Philip Kemble, lead actor and part owner of Covent Garden Theatre, introduced Jewish boxers (typically referred to by contemporaries as 'ruffians') into the pit in order to suppress the riots. Such was the public indignation against these (to use a present-day term) 'bouncers', that the group (led by the noted boxer Daniel Mendoza) were hardly seen in the theatre after the following Monday. Nonetheless letters, pamphlets and satires continued to associate resistance to Old Prices with Jewishness for some weeks. Moreover, the motivations of Kemble became associated with Jewish traits. My thesis, in sum, is that this notion of Jewish influence is a subtle yet significant narrative of the riots, perpetuated by the print media in order to make sense of the riots. Despite the lack of factual veracity, letters and satires speaking to Jewish influence illustrate a powerful virtual construction of OP. So powerful indeed, that Kemble's career prior to taking ownership of Covent Garden theatre became satirically recast as somehow 'Jewish'. This explains, therefore, why Kemble becomes 'Mr Jew Kemble'.

Today, I stumbled across the following letter which is of particular importance to my research because it the only letter I have found (thus far) which illustrates the pervasiveness of the Jewish narrative of OP whilst defending London's Jewish community. Historians are quite used to studying stereotypes and prejudice through sources which seek to marginalise minority or non-domestic groups. Rarely however are we offered a glimpse of these processes from an alternative (rational) perspective. I must admit, I'm rather excited...

The Morning Chronicle, Wednesday, October 18, 1809

For the MORNING CHRONICLE

MR. EDITOR,

Considering the independency and impartiality of your Journal, I flatter myself you will give a corner to the following observations, by setting aside a prejudice that seems to pervade the public mind against the Jews.

I allude to the present question at issue between the Managers of Covent-garden Theatre and the Public; now, Sir, I say if the Managers have been mean enough to cringe to the lowest and worst orders of society, for protecting their imposition, I cannot see why the Jews should be singled out from the rest of the disorderly. Where is the sect to be found that ever was, or are, unanimous in the virtue of their body politic? To find a diversity, we have Mr. Harris to thank, for he has certainly brought forward the dregs of the community; therefore, in justice to Mr. H. we ought to recognise him as leaders of the band. As to the Jews that are admitted by orders, I am sure not one fourth of them are in favour of the Managers, for they have still in memory the usage of Kemble against Braham. Is it then not prejudice, to call in question some of the most honourable characters of the Jews, on account of a few hired fighting fellows. Surely we live in an age of reason; let us not run back from civilization to refer to the blood-stained pages of the dark ages of persecution; let us not be unjust to a Jew, for no other reason than he being a Jew.

Odium is generally levelled by those who can the least account for the antipathy, but the citizen of the world looks impartially for the man.

I am; Sir, your constant Reader,

COSMOPOLITE

EDIT: it is worth adding that the print which adorns the background of my blog is in response to the OP war. Little of the print relates to Jewishness as far as I can tell. But if anyone spots a connection, do tell.

Sunday, 15 May 2011

Flirting with Apocalypse - Part 2: Nukes

Threading clear representational threads through and trends from this vast corpus is not the purpose of this section. Instead, it presents striking examples of how 'the bomb' has been imagined by British cartoonists, as a facet of a wider conversation upon man's flirtation with self-induced apocalypse.

“She came upon a low curtain she had not noticed before, and behind it was a little door about fifteen inches high [...] Alice opened the door and found that it led into a small passage, not much larger than a rat-hole: she knelt down and looked along the passage into the loveliest garden you ever saw”

Much like Lewis Carroll's Alice, a small boy of 1928 peeks with intrigue behind a curtain. He is met with a feast of technological invention, an imagined future of weather control, robots, and communicative media (here 'TELETASTE' stands out as a particularly jovial comic flourish). However among these delights of utopian and egalitarian optimism stands three portentous potentialities – 'THE FINAL POISON GAS?', 'THE FINAL EXPLOSIVE?', 'THE HARNESSED ATOM'?.

Saturday, 7 May 2011

Neurogubbins: some beginnings...

Once the Post Office had done their bit, I plunged into this mysterious world of 'neuroarthistory' and by the conclusion of Onians' introduction I became acutely (and pleasantly) aware that something was amiss. Over the comings months I discussed things at length with a friend who knew more about such things than I (Matthew Thomas, currently studying an MSc in Human Evolution & Behaviour at University College London; follow his musings at http://tangledwoof.wordpress.com/), and clear cracks in Onians' thesis started appearing. Agitated I furiously constructed the following response.

A short caveat. This was a work of catharsis, designed as a means of exhaling the thoughts that were swirling around my mind at the time. It was not designed to be published. And it has not been edited for some months. This then, is snapshot of my mind in late-August/early-September 2010 (when, I must add, I probably should have been spending my time finishing my PhD thesis... and for those who are concerned, fear not. PhD was submitted on time and successfully viva'd). As such there are some aspects of this I would probably change now. And add to. Nonetheless it is a good starting point, and a useful document of how, where and why my life as a neurohumanties skeptic began.

REVIEW

Neuroarthistory: From Aristotle and Pliny to Baxandall and Zeki

John Onians

Yale University Press, 2008

Pp 225. US$40·00. ISBN-978-0-30012-677-8

As it's title suggests, Onians' book has the bold aim of synthesising 'hard' scientific knowledge with the somewhat 'softer' realm of art history. Such work has only recently been made possible, as Onians argues in his introduction, our understanding of the brain has progressed so rapidly in the last third of the twentieth and the first decade of the twenty-first centuries that cultural constructs, the world of signifiers (and signifieds), are no longer sufficient to explain the processes by which works of art were and are created and experienced. 'The use of neuroscientific knowledge as an aid to the study of art', Onians triumphantly writes, 'is now an established practice'. [9]

Onians' positivism is hardly surprising. It was he who coined the term 'Neuroarthistory' in 2005, and the present volume pursues such an application of neuroscientific principles to art developed first in his postgraduate teaching at the University of East Anglia and second in his collaboration with Semir Zeki, the Professor of Neurobiology turned founder of 'Neuroaesthetics' at University College London.

This multidisciplinarity has not gone unnoticed, or indeed passed without significant critique. Raymond Tallis, Emeritus Professor of Geriatric Medicine at the University of Manchester, had led a fierce resistance against such scholarly behaviour. For Tallis, writing in the Times Literary Supplement in a response to A. S. Byatt's neural deconstruction of John Donne's poetry in the same publication, Onians (although not mentioned due to the near simultaneous publication of their work) would be considered not as a pioneering innovator but as one of the growing number of so-called 'neuroscience groupie[s]'. Reductionist, professionally exploitative and prone to 'overstanding', these writers Tallis contends deal in 'neurospeculation, not neuroscience' and in doing so marginalise the rich networks of context and understanding which enliven humanities scholarship. As Tallis concludes [link here]:

As a sub-discipline of neuroaesthetics we would expect Tallis to hold similar reservations about the veracity and utility of neuroarthistory [a small interjection from present me is required here, as, unbeknown to me, Tallis had indeed made a significant pop at Onians at the time I was writing this: see here]. Indeed this essay argues that like Byatt, Onians' thesis suffers fundamentally from a similar misunderstanding of the 'present state of neuroscience'. But before discussing how Neuroarthistory offers a salutary lesson for historians and humanities scholars on the dangers of appropriating neuroscience (and indeed emergent 'hard' scientific processes in general) for their purposes, it is worth outlining the positive values of Onians' study.

Onians makes his aims very clear from the outset. 'The last of our authors, Semir Zeki, claims that artists are often neuroscientists without knowing it. This book', he continues, 'makes a similar claim for writers on art' [13]. Irrespective of the neuroscientific problems associated with this claim, the formulation of his argument is refreshing and at times compelling. His structure involves brief, segmented discussions on the works of major thinkers on art (including notable chapters on Josef Goller, Ernst Gombrich, and Michael Baxandall) covering a period from Aristotle to present day. What is innovative within this chronology is Onians' invocation of theorists not traditionally associated with art, such as Kant, Marx and Freud, and his exploration of how these men (there are lamentably no women) all displayed an underlying and cumulatively developing concern with how the (sub)conscious brain shaped the production of art. Each may have lived in different era of medical and scientific knowledge, but all were keen to postulate on the brains role because they (rightly so, Onians argues) suspected the function of the brain would ultimately (at times read: inevitably) unlock the 'secrets' of art. This synthesis of close readings from works produced by these unlikely actors is achieved with relative ease (with or without the neuroscientific baggage), begging the question of why this position had not been reached previously.

Problems however start to arise, as hinted above, when Onians moves from these more traditional methods of intellectual enquiry into regarding the theorists under discussion as the 'neural subjects' [14] he promises to in his introductory gambit. Although Onians does display caution regarding the fixity of the scientific foundations underpinning neuroarthistory – 'it will constantly change as the knowledge on which it is based is expanded, reinterpreted and revised […] today's knowledge easily degrades into tomorrow's opinion and error' [17] – such comments are at odds with the tenor of his account.

Indeed the closest Onians comes to the tendentious reductionism Tallis accuses Byatt (and neuroaesthetics in general) of is in his neural explanations of how the theories his subjects wrote were arrived at. Passages of this nature conclude each chapter and centre around how environmental factors shaped not the outlook of each subject but there actual neural networks. To do so, Onians invokes the concept of 'neural plasticity' (more on which later), the impact of which he understands thus:

Thus in his discussions of Goller, Onians makes the perfectly plausible claim that Goller's theory of architecture was ground-breaking because improvements in train travel allowed him to not only see a variety of architectural styles, and hence a wide range of 'data', but to see them in more rapid succession than was ever before possible. Even his modestly neuroscientific claim that Goller 'would have unconsciously become more and more sensitive to patterns of variation through time and from place to place' is thoroughly explainable using 'traditional' non-neurological methods. What is most problematic however is when Onians pushes this neurological reading into territory only his neuroscientific/neuroaesthetic framework can explain, such as his claim that:

It is worth reiterating at this point that I am aware that Onians clearly states that he knows the neuroscientific knowledge behind neuroarthistory is liable to change and in the process make neuroarthistorical writings obsolete. Considering this, his taking on of such an endeavour must be applauded. What is problematic, and what I will now move on to show, is that not only has the neuroscience underpinning of Onians' work been challenged since the publication of Neuroarthistory, but it was far more unstable at the time of writing than he recognises. This, I argue, seems to stem from Onians' (fundamentally problematic) positivist perception of scientific knowledge.

The 'plasticity' or 'neuroplasticity' which Onians relies upon, for example, does indeed mean something close to his definition (see above) in scientific parlance. Yet however 'scientific' this definition sounds it means little more, as Vaughan Bell writes, than 'something in the brain has changed', and thus says little about the impact of environmental experience on theories of vision and art. As Bell continues [link here]:

Similarly the concept of 'mirror neurons', central to Zeki's theses and crucial to Onians' understanding of how the brain replicates experience, is far from unchallenged. In short 'mirror neurons' are used to describe the phenomenon, first hypothesised in the 1980s by observations upon macaque brains and quickly imported into understandings of the human brain, of neurons in the motor cortex (ventral premotor cortex) which 'fire' both when the animal/human performs a gesture (say picking up a piece of chalk) and when they see the same gesture being performed. This theory has since proven extremely influential, not least because it purports to hold the proverbial key to learning by sitting alongside pre-existing simulation theory and concepts of neuroplasticity.

But mirror neurons are far from unproblematic. The backlash against their existence may have arrived too late to alter Neuroarthistry, but Onians' statement that 'soon it was realised that humans have even richer neural resources for mirroring' [6-7] is not only vague but represents a crude and ascientific leap between macaques and humans. As the above mentioned paper by Henrich et al. notes, scientists had argued for some time that transferring a biological trait of one species to humans underplays the impact of 'culture-gene coevolution [that] has dramatically shaped human evolution in a manner uncharacteristic of other species' [79]. Or as Tallis writes 'we are different from animals in every waking moment of our lives […] But if we deny this (invoking chimps etc) even in the case of creativity – and the appreciation of works of art – then no distance remains'.

By raising these issues I am not simply criticising Onians for getting his neuroscience 'wrong'. Indeed I warmly congratulate him for attempting, however problematically, to synthesise neuroscience with humanities research. Instead the lesson to be taken from Onians' approach to science is not his mistakes, but his erroneous tendency towards fixity and the cumulative power of science. At no point are the above questions, concerns and debates addressed with respect to scientific principles fundamental to his conclusions, and in their place we are told of the 'surprising precision' with which scientists understand our 'neural resources' [xii]; contestation is not addressed, instead neuroscience is marked by words and phrases such as 'contributing', 'agreed', 'common concern', [5] 'accumulation of knowledge' [5, 7], and 'gradual improvement in the understanding' [12]. To some extent this is true. Knowledge of the brain has improved vastly in the last four decades. However by seeing agreement where there is in fact vigorous debate, Onians is led into making very reductionist and vague statements of scientific 'fact' and the utility of those facts for his study:

The subjectivity of the individual is not, as some have argued, just a social construct. It is embodied in the brain […] Throughout an individual's life it manifests itself in his or her actions, thoughts and products, and, since all the experiences a persons has during their life are liable to affect the formation of their neural networks, to the extent that those experiences can be reconstructed, the subjectivity they produce can also be reconstructed hundreds or even thousands of years after the person in question has died. [14-15]

Indeed the treatment in Neuroarthistory of Onians' chief influence, Samir Zeki, is particularly revealing. Towards the conclusion of Inner Vision (1999) Zeki writes:

Here Zeki invokes discussions earlier in his book of how specific aspects of vision (colour, facial recognition) are disabled by damage to specific areas of the human brain. Hence he does not claim to understand what these areas we have 'pinpoint[ed] with an unimaginable accuracy' are fully capable of, rather that we simply know their basic functional capacity. Zeki's rhetoric is thus cautious, a sentiment extended in his epilogue where he remarks:

What is interesting about this passage is not only that Zeki's neuroscience is subject to debate but that Walsh, like Zeki, sees being 'fruitfully wrong' as part of the scientists job. In contrast Onians may see it as part of his job, as a pioneer of neuroarthistory, to be similarly 'fruitfully wrong' but his discredits Zeki putting his own work in such an unstable category. As Onians writes:

Despite these problems Neuroarthistory is a book of undoubted and admirable ambition. However what Onians describes as the 'defining feature' of his 'approach' (we are told categorically that it is 'not a theory'), namely it's 'readiness to use neuroscientific knowledge to answer any of the questions that an art historian may wish to ask', is misguided [17]. Although neuroscientific knowledge has potential to become a tool in the armoury of humanities scholars, at present the foundations of neuroscience are too unstable and too disputed to be of significant use, and to ignore this volatility, as Onians does, is not only erroneous but potentially dangerous. Indeed I was initially, although with some lingering reservations, convinced by the case made by Neuroarthistory. Yet it took only a few enquiries with colleagues and friends to uncover the shaky foundations of Onians' approach and how his compelling prose and vital capacity for analytical description could cloud and distance the realities of neuroscience and neuroscientific debate from a less inquisitive reader.

Onians acknowledges in his introduction the different pace of scientific and humanities research, and hence the possibility of Neuoarthistory becoming obsolete faster than a 'traditional' work of art history might. This addition is welcome and Onians' bravery and ambition has and should continue to be applauded. Indeed as neuroscientific research continues his position may in fact be vindicated. There is already, for example, the potential (unexplored by Onians) to view the categorisation of the world by the brain alongside the societal urge to stereotype explored in Walter Lippmann's seminal Public Opinion (1922) and the instinctive rationalising of physiognomic perception outlined by Ernst Gombrich ('On Physiognomic Perception', 1960). Nonetheless it should not be ignored that with a little probing the scientific foundations of Neuroarthistory are shown to be far less secure than Onians appears to suggest they are, and thus without significant reappraisal and scaling back of its claims, Onians risks the discrediting of the approach he himself has founded. It is hoped then that in the remaining two books of this neuroarthistorical trilogy the imprecision of neuroscience and the debates over some of the key concepts he uses are addressed. Otherwise, regrettably, neuroarthistory must be considered little more than a pseudo-scientific deception.

Wednesday, 4 May 2011

The Widow

More common were droll satires such as Isaac Cruikshank’s, The Disagreeable Intrusion, or Irish Fortune Hunter Detected (4 September 1795). Here a widow, seduced by an attractive Irish fortune hunter, consents to their marriage only to have her wishes thwarted by the arrest, presumably for polygamy, of her lover. Contrasted with a classical nude portrait, Cruikshank satirises her willing ignorance towards this calculated, charming and affectatious male exploiting the foibles of English elite institutions. He is a criminal and a bigamist, yet 'The Disagreeable Intrusion' will only briefly rob him of his liberty and delay his enrichment. He is thus not the fool. That honour is taken by the widow, who, shocked by the 'intrusion' rather than appalled at her deception, would willingly marry a rogue rather than not marry at all.

More common were droll satires such as Isaac Cruikshank’s, The Disagreeable Intrusion, or Irish Fortune Hunter Detected (4 September 1795). Here a widow, seduced by an attractive Irish fortune hunter, consents to their marriage only to have her wishes thwarted by the arrest, presumably for polygamy, of her lover. Contrasted with a classical nude portrait, Cruikshank satirises her willing ignorance towards this calculated, charming and affectatious male exploiting the foibles of English elite institutions. He is a criminal and a bigamist, yet 'The Disagreeable Intrusion' will only briefly rob him of his liberty and delay his enrichment. He is thus not the fool. That honour is taken by the widow, who, shocked by the 'intrusion' rather than appalled at her deception, would willingly marry a rogue rather than not marry at all.These names, dates, and descriptions found in the RBT records tell us little beyond what was formally required to be on such official documents (leases et al). Nonetheless the patterns present are of interest. As was the case for High Halstow (Kent) it is notable how female possession of a property was in the early modern period a means by which families could retain ownership of that property. It is also of note how, once again, female ownership at this Essex estate ceases from sometime in the early-nineteenth century.

Monday, 2 May 2011

Flirting with Apocalypse - Part 1: Christmas

This morning I've been working on a group entitled 'Flirting with Apocalypse', which plans to go beyond the 20th century symbol of doomsday, the atomic bomb, and explore through cartoons man's relationship with what Al Gore famously called 'our only home'. Themes such as rural erosion, consumerism, oil spills, green politics and natural disasters will be covered, with the aim of offering students a starting point towardss thinking about how man's construction of their world (not only physically, but also mentally) impacts upon the environment we all inhabit.

Over the coming weeks I plan to share some preliminary findings here. And today I offer some thoughts Christmas:

Saturday, 30 April 2011

Will, Kate, and Cannadine.

This of course does not render Cannadine's thesis incorrect. Although his predictions of monarchical decline may seem on 30th April 2011 a little premature, #RW2011 is surely little more than a sticking plaster. Of greater importance perhaps, 'the wedding' alerts us to the trouble historians can run into (though Cannadine carefully litters his thesis with caveats) when predicting the future. Moreover it reminds us of the intoxicating power such public displays of 'ornamentalism' can still have on the 'public imagination'. For as an expression of everything 'ornamentlism' is, the wedding was also everything the Queen cherishes - as Cannadine writes 'medals, uniforms, decorations, investitures and ceremonial'. Combine that with a Clarence House administration more technologically savvy than most commentators give them credit for (see The Royal Channel), and suddenly we have a powerful 'ornamentalism' operating with an unprecedented communicative pervasiveness.

This of course does not render Cannadine's thesis incorrect. Although his predictions of monarchical decline may seem on 30th April 2011 a little premature, #RW2011 is surely little more than a sticking plaster. Of greater importance perhaps, 'the wedding' alerts us to the trouble historians can run into (though Cannadine carefully litters his thesis with caveats) when predicting the future. Moreover it reminds us of the intoxicating power such public displays of 'ornamentalism' can still have on the 'public imagination'. For as an expression of everything 'ornamentlism' is, the wedding was also everything the Queen cherishes - as Cannadine writes 'medals, uniforms, decorations, investitures and ceremonial'. Combine that with a Clarence House administration more technologically savvy than most commentators give them credit for (see The Royal Channel), and suddenly we have a powerful 'ornamentalism' operating with an unprecedented communicative pervasiveness.Friday, 29 April 2011

Land and Gender

Thursday, 28 April 2011

Tradition

Though decided on the AV debate - #Yes2AV - following the political mudslinging over the recent weeks has proven curiously captivating.

Though decided on the AV debate - #Yes2AV - following the political mudslinging over the recent weeks has proven curiously captivating.This morning I stumbled across this interview of Baroness Warsi conducted by the ever pugnacious Adam Boulton. Surprisingly, and not merely because he was on 'my side', Boulton came across rather well, particularly during his dissection of what Warsi classified as 'tradition' (She did not actually use the word, but statements such as 'fundamental principles' and 'generations have fought for' suggest what she is getting at. Well at least it did for me).

Two semantic problems arise from this which probably should trouble us more than they do.

First, how old is 'tradition'? Warsi was appealing (erroneously of course) to a tradition beginning around 1945, thus disregarding from tradition a long history of parliamentary adaptation. In a similar vein the Old Price rioters at Covent Garden theatre during the Autumn of 1809 classified the rights of Englishmen to public entertainments as existing since 'time immemorial'. In the same way that Milton's Areopagitica claimed press freedoms to be inalienable,  the OP rioters had a dislocated and distorted sense of what terms such as 'tradition' and 'ancient' meant. Equally during a period of acute food shortages in the early-nineteenth century, Justice Kenyon prosecuted against forestallers and regrators. These practices, which inflated food prices artificially, were perfectly legal. However common law and custom stated that they were not, and thus many ignored the 1771 legislation repealing prohibitions on these practices. Kenyon, under the Cruikshankian gaze, became a popular hero, a defender of natural rights. Yet, there is more, the legislation making forestalling and regrating illegal was neither ancient nor natural but had clear sixteenth century legislative origins.

the OP rioters had a dislocated and distorted sense of what terms such as 'tradition' and 'ancient' meant. Equally during a period of acute food shortages in the early-nineteenth century, Justice Kenyon prosecuted against forestallers and regrators. These practices, which inflated food prices artificially, were perfectly legal. However common law and custom stated that they were not, and thus many ignored the 1771 legislation repealing prohibitions on these practices. Kenyon, under the Cruikshankian gaze, became a popular hero, a defender of natural rights. Yet, there is more, the legislation making forestalling and regrating illegal was neither ancient nor natural but had clear sixteenth century legislative origins.

Tradition then is a complex beast. And depends on the perspective of those who claim something or other to be traditional. Indeed as environmental historians are keen to tell us, there is nothing ancient or traditional about any of this. Human existence, Bill McKibben notes, is to the lifespan of the Earth but a blink of the eye.

Second, whose tradition is tradition? This may seem a very obvious point, but if 'tradition' has chronological problems it is also impacted upon by gender, class, nationality, faith et al. This is exemplified by returning to our forestallers and regrators - for 'the people' (I use that word begrudgingly, with an awareness of the huge problems it entails...) treating food as a special case, as outside of market forces, was customary; for the acolytes of Adam Smith on the other hand food was just another product, another unit to be monetised (and so followed land, labour and, in the present day, carbon - see Doreen Massey's beautiful essay on such matters here).

For Warsi and many in the #No2AV camp, 'tradition' is associated with post-war frugality (both intellectually and financially), settling and stoicism. For many in the #Yes2AV camp, like myself, 'tradition' is something more theoretical, something more timeless (at least in theory, it can, I guess, never be so in reality) - that being a simple belief in individual agency and in a rejection of clannish traditions based upon words enshrined upon paper which one may not question.

Tradition then is the very rejection of tradition. And I suspect this definition (if we swap over the two traditions) nicely encapsulates where Warsi stands on the issue too.

Wednesday, 27 April 2011

Cruikshank in public

The work of Isaac Cruikshank has formed the crux of my intellectual life for nearly four years (one of his most lively and detailed prints adorns the background of this very blog - see the record at the British Museum collections). As a result my talk focused on why I see Isaac as an important figure in the history of satirical printing - namely because, unlike James Gillray (whose work tends to be held up

as representative of the trade at the time), Isaac rushed his etchings, made mistakes, lacked consistency in style, couldn't draw likenesses, and was generally a bit (to use my favoured antipodean term of slander) 'average'. Perhaps I'm being a little harsh on Isaac. He did after all teach a young George Cruikshank all he knew (well, maybe I'm exaggerating now...). But my point nonetheless is and was that artists such as Isaac Cruikshank are representative of the trade, not supreme masters such as Gillray.

as representative of the trade at the time), Isaac rushed his etchings, made mistakes, lacked consistency in style, couldn't draw likenesses, and was generally a bit (to use my favoured antipodean term of slander) 'average'. Perhaps I'm being a little harsh on Isaac. He did after all teach a young George Cruikshank all he knew (well, maybe I'm exaggerating now...). But my point nonetheless is and was that artists such as Isaac Cruikshank are representative of the trade, not supreme masters such as Gillray.Perhaps I underestimated my audience. But to be frank I expected a backlash. I expected the idea that artistic quality would not 'win out' to be dismissed, decried, and pooh-poohed. Instead the audience were very accepting of my remarks, and saw it as perfectly logical that we have to (to paraphrase the work of Adrian Johns on books) forget what we know about cartoons in the present when studying the same medium in the past, because, in sum, the two are actually not the same medium at all.

It has troubled me for a number of years that historians seem unable to make this leap of faith. And it surprised and delighted me in equal measure to find that those members of the public who made their way to The Cartoon Museum that night had indeed, it seems, made that leap. Or had they? Are we as historians taught to tie our sources together too neatly? Are we, despite Butterfield's warnings of eight decades ago, inclined towards Whiggish narratives of the past? Or, more controversially perhaps, has the influence of art-historians on the field of Golden Age satirical printing inculcated this Whiggishness?

My attempts to explore these problems, and much more, will be explored here.