Blogger has been good to me. However as begin to demand more flexibility from my blogging experience, I begin to tire of the restrictions I find here.

With that in mind I've migrated my blog to http://cradledincaricature.wordpress.com/. First post went up yesterday > http://cradledincaricature.wordpress.com/2011/06/12/soja-geography-la-sarthe/.

Information relating to the Cradled in Caricature symposium will remain here for the meantime, though will to be migrated from 20 June onwards. And for those who are interested, the #CiC liveblog on 20 June will be simulcast between the new CiC wordpress site and @cincaricature. Exciting times!

Dr B

Monday, 13 June 2011

Wednesday, 8 June 2011

#CiC – adverts and taxonomies

One of the most exciting events taking place at Cradled in Caricature is a workshop entitled 'Create Your Own 1920s Advert'. This is to be led be two postgraduates from the School of History – Michael Kliegl and Rebecca Farmer – and will explore aesthetic, psychology and advertising in order to understand how and why advertisements are so wedded to stereotypes of character. After dividing into groups participants will be asked to make their own advertisements, and (here is the really fun bit) will be offered big pens, jumbo stick notes and boards in order to make them.

Despite there being a clear intellectual rationale behind this workshop focusing on cigarette advertising in the 1920s (see abstract here), we felt that spreading posters containing the Marlboro man around campus may have attracted some negative attention from the powers that be at the University of Kent. We therefore had to find an alternative advertising campaign that was both well known internationally and clearly associated the product in question with making people a 'better' man/woman. After some thought, the only campaign we could think of was what you see below. As Terry Norton says on Knowing Me Knowing You with Alan Partridge “people will always want to look at lovely ladies”...

Cradled in Caricature will take place on Monday 20 June, at Woolf College, University of Kent, Canterbury.

The full programme can be found here.

For inquiries or further information please contact me at cradledincaricature@gmail.com or twitter.com/cincaricature.

Despite there being a clear intellectual rationale behind this workshop focusing on cigarette advertising in the 1920s (see abstract here), we felt that spreading posters containing the Marlboro man around campus may have attracted some negative attention from the powers that be at the University of Kent. We therefore had to find an alternative advertising campaign that was both well known internationally and clearly associated the product in question with making people a 'better' man/woman. After some thought, the only campaign we could think of was what you see below. As Terry Norton says on Knowing Me Knowing You with Alan Partridge “people will always want to look at lovely ladies”...

Cradled in Caricature will take place on Monday 20 June, at Woolf College, University of Kent, Canterbury.

The full programme can be found here.

For inquiries or further information please contact me at cradledincaricature@gmail.com or twitter.com/cincaricature.

Tuesday, 7 June 2011

Memory and Remembrance - Part 1: The Fallen

The second teaching aid I am creating for the British Cartoon Archive's JISC funded CARD project is a selection of cartoons on the theme of 'Memory and Remembrance'. Inspired by both the work and teaching of my colleague Dr Stefan Goebel this group looks at the reappropriation of symbols generated by heroism, conflict and loss in British cartoons.

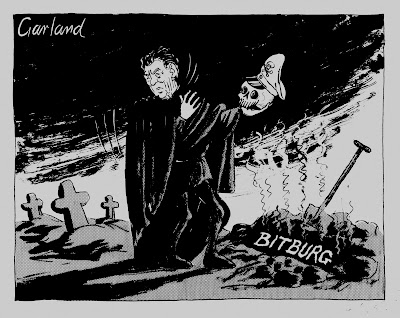

One sub-theme within this group looks at physical and imaginative memories of 'The Fallen' and how they both shape and are manipulated by politics and culture. A taster of this work can be found below...

(c) British Cartoon Archive, University of Kent, Nicholas Garland, Daily Telegraph, 30 Apr 1985.

As Jay Winter writes, however we might wish to believe otherwise, remembrance is political. When US President Ronald Reagan visited West Germany in Spring 1985 to mark the 40th anniversary of VE Day his choice of locations (and indeed those of his host Chancellor Helmut Kohl) were consciously political, chosen to foster reconciliation by establishing the events of World War Two as a shared tragedy (these one time combatants were now, of course, allies). The itinerary however included a visit to Kolmeshohe Cemetery at Bitburg, a site at which 49 members of the Waffen SS were buried. When this was leaked to the press a huge controversy ensued (interestingly Reagan’s chief of staff, Michael Denver, had failed to notice the names on the graves on a preparatory visit due to heavy snowfall). Despite protests from Jewish Americans, Reagan pressed on with the visit and joined Kohl on 5 May 1985 to lay wreaths at a wall of remembrance.

The visit was ‘saved’ by former Nazi Luftwaffe pilot and later NATO General Johannes Steinhoff, who in an impromptu act reached and shook the hand of his former belligerent General Matthew Ridgway, commander of the 82nd Airborne during World War Two. This, alongside a well pitched speech from the ever theatrical Reagan, gained the visit unexpected credit. Garland anticipates how Reagan was expected to emerge from the Bitburg, using the exhumation of Yorick in Shakespeare’s Hamlet to mock Reagan (who famously was a Hollywood actor before turning to politics). While Hamlet touchingly remembers the court jester he once knew, Reagan turns in horror from the Nazi before him (which, as a side note, is possibly a visual quotation to the Nazi villains in Steven Spielberg’s 1981 film Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, one of the highest-grossing films of the decade).

One sub-theme within this group looks at physical and imaginative memories of 'The Fallen' and how they both shape and are manipulated by politics and culture. A taster of this work can be found below...

(c) British Cartoon Archive, University of Kent, Nicholas Garland, Daily Telegraph, 30 Apr 1985.

As Jay Winter writes, however we might wish to believe otherwise, remembrance is political. When US President Ronald Reagan visited West Germany in Spring 1985 to mark the 40th anniversary of VE Day his choice of locations (and indeed those of his host Chancellor Helmut Kohl) were consciously political, chosen to foster reconciliation by establishing the events of World War Two as a shared tragedy (these one time combatants were now, of course, allies). The itinerary however included a visit to Kolmeshohe Cemetery at Bitburg, a site at which 49 members of the Waffen SS were buried. When this was leaked to the press a huge controversy ensued (interestingly Reagan’s chief of staff, Michael Denver, had failed to notice the names on the graves on a preparatory visit due to heavy snowfall). Despite protests from Jewish Americans, Reagan pressed on with the visit and joined Kohl on 5 May 1985 to lay wreaths at a wall of remembrance.

The visit was ‘saved’ by former Nazi Luftwaffe pilot and later NATO General Johannes Steinhoff, who in an impromptu act reached and shook the hand of his former belligerent General Matthew Ridgway, commander of the 82nd Airborne during World War Two. This, alongside a well pitched speech from the ever theatrical Reagan, gained the visit unexpected credit. Garland anticipates how Reagan was expected to emerge from the Bitburg, using the exhumation of Yorick in Shakespeare’s Hamlet to mock Reagan (who famously was a Hollywood actor before turning to politics). While Hamlet touchingly remembers the court jester he once knew, Reagan turns in horror from the Nazi before him (which, as a side note, is possibly a visual quotation to the Nazi villains in Steven Spielberg’s 1981 film Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, one of the highest-grossing films of the decade).

Sunday, 5 June 2011

#CiC - heroes and villains

A panel called 'Heroes and Villains' promises to offer a vibrant exploration of the topics central to the symposium. Jacob Bradsher will investigate what makes a science-fiction villain, whilst Caleb Turner will ask "how do we magnify bodily attributes through caricature and why as viewers do we need this exaggeration to better realise a sense of meaning or truth, i.e. superheroes?".

Their abstracts (below) inspired the above poster which now can be found dotted across UKC.

The full programme can be found here.

For inquiries or further information please contact me at cradledincaricature@gmail.com or twitter.com/cincaricature.

Their abstracts (below) inspired the above poster which now can be found dotted across UKC.

Jacob Bradsher

Villainous caricature in Science-fiction literature, film, and art is rooted firmly in the portrayal of villains in Victorian literature. The limitations of the human mind to conceive of truly unique villainous characteristics is obvious when these comparisons are made. Despite the radical design of some twentieth century visions of space-villains and alien overlords, the similarities between them and the likes of Dickensian illustrations are striking.

I would like to investigate what makes a ‘villain.’ That is, I am going to explore the facial features, actions, modes of speech, and overall physical appearance of what has been considered villainous in Victorian literature (such as the illustrations of Phiz and Cruikshank) and how that has carried over into genres like science fiction and the portrayal of its antagonists (Star Wars, Titan A.E. etc.).

It’s mostly a compare/contrast project, but I don’t want to simply show the similarities and differences in illustrations and character designs. Roughly, I would be using Dickensian canon as a starting point, then I would move to the golden age of American comic books, then onto modern movies and science fiction literature to explicate the relationship between the genres and periods.

Basically, I would like to explore the relationship between what stereotypical villainous characteristics are immediately available to us a humans and those that we project onto perceived villains of the future. The caricatures of Dickensian villains are easily identifiable compared to some of those featured in Sci-Fi productions, but there are also striking similarities.

Caleb TurnerCradled in Caricature will take place on Monday 20 June, at Woolf College, University of Kent, Canterbury.

How do we view bodily depictions through caricature? The cartoonist Lenn Redman has described caricature as: “An exaggerated likeness of a person made by emphasising all of the features that make the person different from everyone else. It is not the exaggeration of one’s worst features. This is a carry over from the days, 100 years and more ago, when humour was almost always based on cruelty and when the caricaturist’s intent was to insult his subject… Many people think that a caricature is necessarily a graphic distortion of a face. Not true! The essence of a caricature is exaggeration – not distortion. Exaggeration is the overemphasis of truth. Distortion is a complete denial of the truth.

In this light, caricature should no longer be (traditionally) viewed as simply a form of mockery through grotesquery, but more so as magnifying the truth through over-emphasising the defining physical boundaries – constituting an individual body – to their absolute limits. One type of body in particular that utilises this process to great effect is the superhero figure, being an intensely graphically illustrated physicality.

To exaggerate a super-body is to take one’s most distinguishing features, (i.e. pointed ears, thick eyebrows, thin chin, warped smile and sharp teeth for the face of ‘The Green Goblin’; huge, thick fists attached to tree-trunk muscular arms for the hands of ‘The Incredible Hulk’) and streamline them to depict just how ‘different from everyone else’ they are. To caricaturise these individuals is to then ‘magnify’ the limits of truth associated with them even further (i.e. a display of ‘invulnerability’ in the sheer size of Superman’s solid chest, or ‘intelligence’ with Brainiac’s brain bulging outwards from the top of his head).

What does this overemphasis of truth (rather than distortion) achieve in conveying meaning to us through the process of caricature? The superhero body is itself an expression of deliberately exaggerated characteristics, intended to evoke from only a marginal threshold of interpretation, consequently having a specific series of connotations attached to it. These constructed figures portray specific ideas, but they are designed to be among the most recognisable depictions of these ideas: they are presented as being an absolute epitome or incarnation of such concepts.

How, then, is this ‘magnification’ of super-bodily attributes useful as a process for understanding and why as viewers do we need it to better realise a sense of meaning or truth?

The full programme can be found here.

For inquiries or further information please contact me at cradledincaricature@gmail.com or twitter.com/cincaricature.

Thursday, 2 June 2011

Richard Rodger: Space, place and the city: a simple anti-GIS approach for historians.

Phase III of the City and Region project will include significant GIS work as a means of displaying rent data in a dynamic visual format.

Watching this Digital History seminar at the IHR is therefore part of my job. Thus I thought I'd share.

Watching this Digital History seminar at the IHR is therefore part of my job. Thus I thought I'd share.

Watch live streaming video from historyspot at livestream.com

The Efflorescence of Caricature

Just a small post in reponse to my review of Todd Porterfield (ed.), The Efflorescence of Caricature: 1759-1838 (London, Ashgate, 2011) appearing in the IHR's Reviews in History (http://www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/1084).

First, I wanted to praise the IHR for providing such a reactive and reflexive space as RIH. I first saw this book at BSECS '11 (which was in early January), asked for a copy days after, recieved it just a few days after that, and having only submitted the review to them in mid-April it is already up. So huge kudos to the IHR.

Second, I wished to add that I really did enjoy this book even if at times my review comes across as a little negative. There were some moments of signifcant frustration with the 'representation without physical grounding' direction some of the contributions took (my flatmate can verify to one particular moment where the book was in risk of being hurled out of a room - I'm sure you can guess which from the review...), but the willingness of Porterfield in particular to break the study of graphic satire out of the shackles of orthodoxy must be applauded. So if you like your history to be both annoying and inventive (comes with the territory of being radical I guess), then pick up a copy.

First, I wanted to praise the IHR for providing such a reactive and reflexive space as RIH. I first saw this book at BSECS '11 (which was in early January), asked for a copy days after, recieved it just a few days after that, and having only submitted the review to them in mid-April it is already up. So huge kudos to the IHR.

Second, I wished to add that I really did enjoy this book even if at times my review comes across as a little negative. There were some moments of signifcant frustration with the 'representation without physical grounding' direction some of the contributions took (my flatmate can verify to one particular moment where the book was in risk of being hurled out of a room - I'm sure you can guess which from the review...), but the willingness of Porterfield in particular to break the study of graphic satire out of the shackles of orthodoxy must be applauded. So if you like your history to be both annoying and inventive (comes with the territory of being radical I guess), then pick up a copy.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)